In November 2017, a study into the effectiveness of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) caught international attention for raising questions about the benefits of angioplasty and stenting. The study, Objective Randomised Blinded Investigation With Optimal Medical Therapy of Angioplasty in Stable Angina (ORBITA), concluded there was no benefit for patients with stable angina who underwent PCI.

After patients were given medical therapy and either PCI or a placebo sham procedure, no difference was shown in their exercise times on a treadmill six weeks later. The study included a low-risk group of 200 patients with single-vessel stenosis and stable angina.

Patients with unstable angina, multi-vessel disease or those with high-risk conditions were not included in ORBITA. However, the “spin” from the ORBITA trial spread like wildfire through social media. Many mainstream media headlines implied falsely that the study demonstrated no benefit to stenting for virtually everybody, a message that leaves patients, referring physicians and cardiologists confused.

“This study adds little to the body of information that we have about who is the appropriate candidate for PCI,” said Steven Kindsvater, MD, an interventional cardiologist and Vice Chairman of Cardiovascular Medicine at Baylor Scott & White The Heart Hospital – Plano. “The headlines suggest nothing needs to be done invasively in the cath lab and stents aren’t required, which is clearly wrong. There are many scenarios where stents are beneficial.”

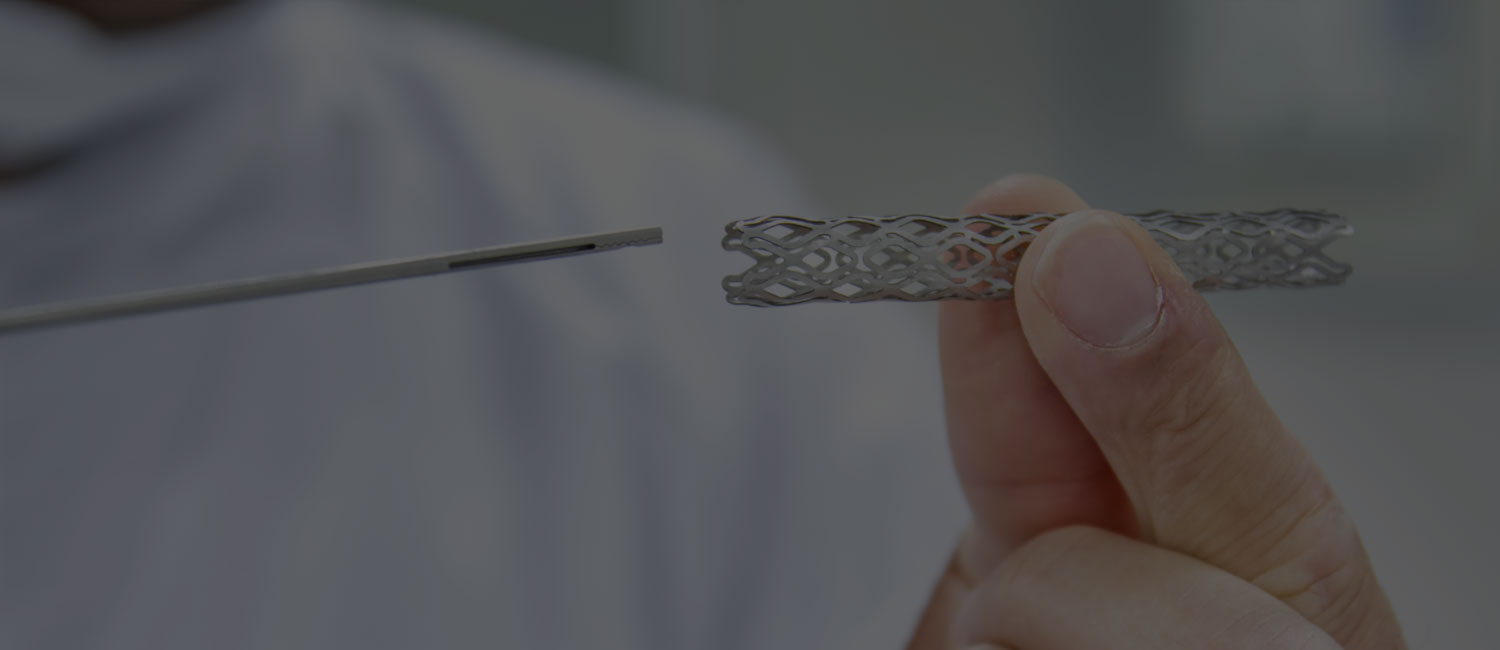

First, stenting is a lifesaving therapy for patients with acute coronary syndromes, including ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina. These patients have urgent needs for revascularization and a high short-term risk of heart attack or death.

Second, stents are beneficial for individuals who have high-risk stress test results or continue to have angina or an angina equivalent despite optimal medical therapy.

“In stable patients with angina, the decision on whether to take a patient to the cath lab is already based on maximum or optimal medical therapy and stress tests that show high-risk results despite medical therapy,” Dr. Kindsvater said. “Those concepts are already part of the appropriateness criteria for heart catheterization. For me, the ORBITA trial reinforces that not stenting is OK in some patients—but ‘some patients’ in this case represent only about 5-10 percent of all patients that go to the cath lab. In other words, 90-95 percent of patients have compelling reasons for stenting.”

Medical therapy is effective in controlling angina, including medicines such as nitrates, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers and ranolazine.

“Medical therapy sounds great, but in the real world, 30 percent of patients fail to take their meds just one month after it is prescribed, and by one year 80 percent of patients aren’t taking medications,” Dr. Kindsvater noted.

Many factors contribute, most notably medication’s cost, inconvenience and side effects (fatigue, weakness, dizziness, sexual dysfunction, etc.).

Results from non-invasive stress tests and fractional flow reserve (FFR) measurements in the cath lab help identify those who would benefit from intervention. Presented at the same conference as ORBITA, the three-year results of the FAME-2 trial seem to be resonating very well with interventional cardiologists.

“There’s no guesswork with FFR. The FAME-2 results are compelling, teaching cardiologists that when we use FFR in the cath lab to guide stenting or not stenting, the patients benefit, and it’s a long-lasting benefit,” Dr. Kindsvater said.

One of the limitations of ORBITA was the short follow-up, just six weeks after the procedure.

“This timeframe [six weeks] is too short to draw conclusions,” Dr. Kindsvater said. “In my experience after several thousand PCI procedures, it takes a few months for patients to maximize the symptomatic benefit of PCI.”

Another major flaw of ORBITA is that 27 percent of patients actually stented in ORBITA should not have been stented based upon established FFR criteria from FAME-2.

“We already know that medical therapy is preferred when the stenosis is not bad with an FFR > 0.80 from FAME-2 and before that the FAME trial,” Dr. Kindsvater said. “On the other hand, when the FFR is < 0.80, medical therapy is clearly not as good as stenting.”

A newer technology – FFR derived from computed tomography (FFR-CT) – is also currently being studied at Baylor Scott & White The Heart Hospital – Plano as a potential tool to more accurately assess who should be a candidate for stenting prior to taking the patient to the cath lab. With FFR-CT, physicians can see FFR calculations for the entire heart with a single CT scan.

“FFR-CT is poised to be a transformative technology, which could significantly reduce the number of invasive procedures that patients currently undergo,” Dr. Kindsvater predicted.

Ultimately, research studies from a variety of sources, including studies on technology like FFR-CT and studies like ORBITA, help guide decisions about patients who may benefit from PCI and those who may benefit from medical therapy alone.

“Nothing has really changed after ORBITA,” Dr. Kindsvater said. “We still know that many people can be treated medically, and on the flip side, many still greatly benefit from stenting. When appropriately selected, patients who undergo PCI have a better quality of life, take less medication and, in some instances, it can actually prevent heart attack or death. I am excited about the next ten years. I think technology will fine-tune exactly which patients need PCI.”